Every year, thousands of women from Nigeria move to Dubai seeking opportunity. Some find work in retail, hospitality, or domestic service. Others enter roles that are harder to talk about openly - including escort work. The term escort girl Dubai often brings up stereotypes, but behind the label are real people navigating complex economic pressures, cultural dislocation, and survival strategies in a city that rewards ambition but rarely offers safety nets.

It’s easy to confuse different types of companionship services in Dubai. While some women work independently, others are connected to agencies that market them under labels like twink escort dubai. These terms, though often used in online ads, rarely reflect the full story. A Nigerian woman working as an escort isn’t just fulfilling a fantasy - she’s paying for her sister’s tuition back home, covering medical bills, or saving to open a small business. The work is risky, legally gray, and emotionally taxing, but for many, it’s the only path that offers immediate financial returns.

Why Dubai? Why Nigeria?

Dubai doesn’t issue work visas for escorting. That’s the official line. But the city’s economy runs on informal labor - cleaners, drivers, nannies, and companions - many of whom are undocumented or on tourist visas. Nigerian women, in particular, are drawn here because of established diaspora networks. Lagos and Abuja have agencies that connect young women with recruiters in the Gulf. These recruiters promise high-paying jobs as models, secretaries, or nannies. The truth often emerges only after arrival.

Nigeria’s economic crisis plays a big role. Inflation hit 33% in 2024. The naira lost over 60% of its value against the dollar in two years. Graduates with degrees in engineering or nursing earn less than $100 a month. Meanwhile, a woman in Dubai can earn $3,000 to $8,000 a month working as a companion - even if the work isn’t advertised as such. The difference isn’t just money; it’s dignity. It’s the ability to send a child to a private school, buy medicine without waiting in line, or pay off a family debt that’s been dragging them down for years.

Who Are the Women Behind the Labels?

Not all women in this space are the same. Some are students on short-term visas, working part-time to fund their degrees. Others are single mothers with no support system. A few are entrepreneurs who built their own client lists and now hire other women. The term escort girl Dubai flattens all of them into one image - usually one shaped by Western media or adult websites.

There are Nigerian women who work with clients from the Gulf, Europe, and Asia. Some prefer long-term arrangements. Others do short, discreet sessions. A few have learned to navigate the legal gray zones by posing as personal assistants or travel companions. The clients vary too - expat businessmen, local Emiratis, tourists from Russia or China. One woman I spoke with said her most regular client was a retired German engineer who paid her to accompany him to museums and dinners. He never asked for more. She said he treated her like a daughter.

These aren’t stories of exploitation alone. They’re stories of adaptation. Of women using whatever tools they have to survive in a system that doesn’t see them as full human beings - until they’re needed for something private, intimate, or convenient.

The Role of Language and Appearance

Marketing plays a huge part in who gets seen and who gets paid. Online platforms use terms like dubai arab escort or eurogirls dubai escort to attract specific types of clients. These labels aren’t just descriptive - they’re performative. They shape expectations. A Nigerian woman with lighter skin or European features might be marketed as an eurogirls dubai escort, even if she was born in Port Harcourt. A woman who speaks fluent Arabic or dresses modestly might be labeled a dubai arab escort, regardless of her nationality.

This racialized marketing isn’t unique to Dubai. It exists in every global city with a sex tourism economy. But in Dubai, it’s amplified by the city’s obsession with image. A woman’s value is often tied to how well she fits a fantasy - not her skills, her education, or her personality. This leads to painful choices. Some women dye their hair, alter their accents, or even wear contact lenses to match the profile clients are looking for. One woman told me she started wearing wigs because her natural hair was deemed “too African” by her agency. She didn’t say it with anger. She said it with resignation.

The Legal and Social Risks

Dubai’s laws are strict. Prostitution is illegal. Soliciting or advertising sexual services can lead to deportation, jail time, or both. Women caught in raids are often treated as criminals, not victims. Many don’t have legal representation. Some are held in detention for months while their cases drag on. Their families back home rarely hear from them.

Even when women aren’t arrested, they live under constant threat. Landlords can evict them without notice. Phone numbers get blocked. Bank accounts get frozen. Clients sometimes refuse to pay or threaten to expose them. There’s no union, no hotline, no government agency to turn to. The only support often comes from other women in the same situation - sharing safe addresses, warning each other about dangerous clients, pooling money for lawyers.

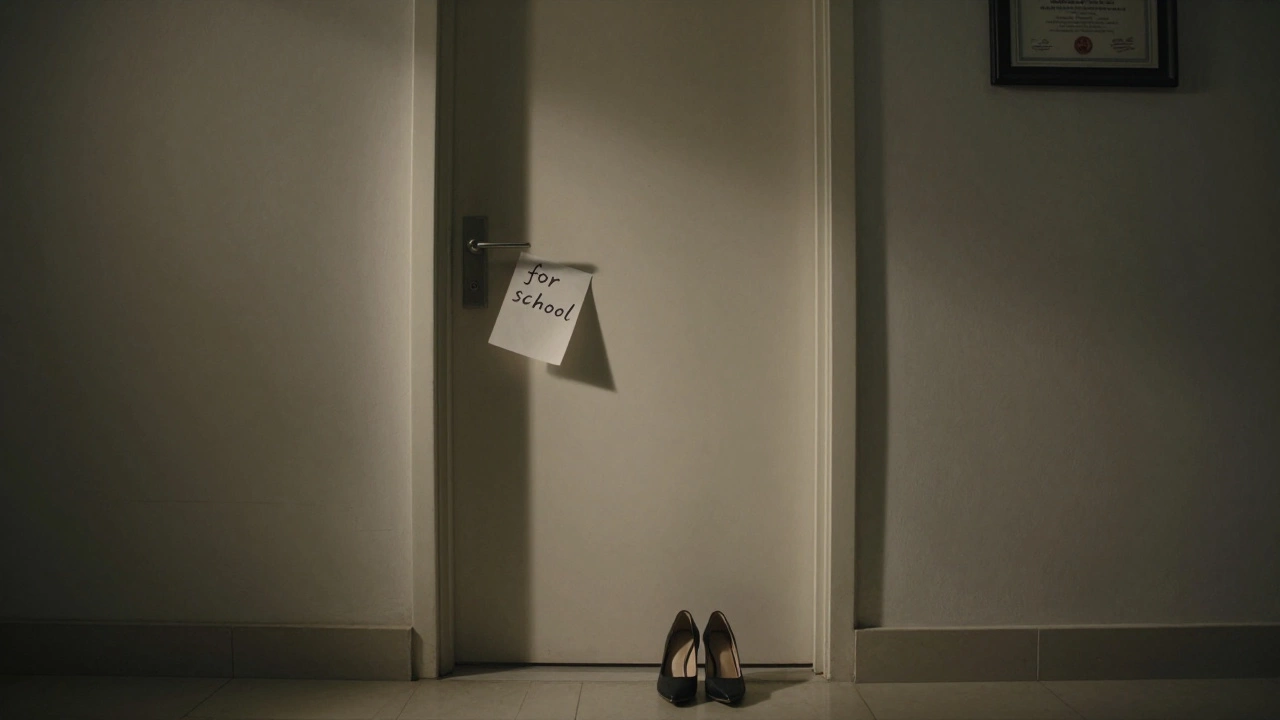

And then there’s the stigma. In Nigeria, women who work abroad in this field are often labeled as “fallen.” Their families are shamed. Their names are erased from family trees. Some women cut off contact with home entirely. One woman I met in Sharjah hadn’t spoken to her mother in four years. She sent money every month, but she didn’t tell her how she earned it. “She thinks I’m a nurse,” she said. “That’s enough.”

What Happens When They Leave?

Not everyone stays. Many leave after a year or two - either because they’ve saved enough, or because they got tired of the fear. Some return to Nigeria and start businesses. One woman I met in Lagos opened a beauty salon using money she saved in Dubai. Another bought a small apartment and rents out rooms to other women who are trying to leave the same life she did.

But not all returns are successful. Some women come back with trauma, debt, or no savings at all. Without support, they’re vulnerable to being pulled back into the same cycle. A few have started small NGOs to help others transition out of the industry. They offer counseling, legal aid, and vocational training. But they operate quietly. No one wants to draw attention to the problem.

Is There a Better Way?

Dubai doesn’t need to ban escort work to fix this. It needs to offer real alternatives. Fair wages for domestic workers. Access to banking for undocumented residents. Legal pathways for skilled migrants. Right now, the system forces women into the shadows because it refuses to see them as anything other than commodities.

Changing that won’t be easy. But it starts with seeing these women for who they are - not as stereotypes, not as keywords in an ad, but as people making impossible choices in a city that offers wealth but no safety. The next time you hear the term escort girl Dubai, ask yourself: who is she? And what would you do if you were her?