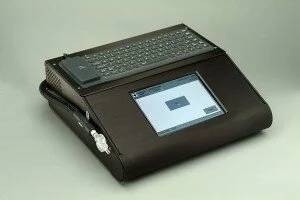

NPAS DataMaster DMT

You’ve just been arrested for drunk driving and the police officer asks you to blow “long and steady into the machine until told to stop.” Why did the drunk driving task force officer use that peculiar language?

Well, it may just be that the officer is trying to justify his decision to arrest you for drunk driving by making sure that your breath test is over the legal limit. A DUI cop can influence the breath test results simply by getting you to blow longer and harder than necessary to meet the minimum sample requirements.

Scientific studies have shown that the longer you blow the higher your go – ALWAYS.[i] The difference between a long blow and a short blow can be as high as .04 and this can mean the difference between guilty and not-guilty.[ii]

According to a white paper[iii] written by attorney Tom Workman[iv] “Since the police officer controls the volume of each sample, and the volume is highly correlated to the reported amount of alcohol, then the breath testing process is a subjective process, and not an objective process.[v]”

Mr. Workman studied more than 100,000 breath tests in Florida and concluded that there was typically a .02 degree of difference between test one and test two and that this .02 difference was attributable to the length of the blow. As explained below, this .02 difference was at the low end of what Dr. Simpson found.

The reason a longer blow creates a higher breath test result is because breath testing indirectly tests a person’s blood alcohol level. Consequently, things that impact a person’s lung function, such as age or disease, may also impact a breath test result.[vi]

One reason lung function might impact a breath test is that with breath testing there is a belief that the alcohol in the “deep lung air” is at equilibrium with the alcohol in the blood.

Another reason lung function might impact a breath test is that with breath testing there is also a belief that the ratio between alcohol in the breath and alcohol in the blood is 2100/1. This is called the partition ration.

Depending on you person’s age, gender, health and many other factors, when applied to your breath test both assumptions may be wrong.

Breath Pattern Problems with Breath Testing:

Barone w/A.W. Jones 2008

Regarding breathing patter, A.W. Jones, one of the world’s foremost experts on the subject has said this:

“The subject’s manner and mode of breathing just prior to providing breath for analysis can significantly alter the concentration of alcohol in the resulting exhalation. Hyperventilation . . . lowers the breath alcohol concentration by as much as 20% compared with a single moderate inhalation and forced exhalation used as control tests. “Holding breath for a short time (20 seconds) before exhalation increases the alcohol concentration in exhaled air by 15%.[vii]”

In 2003 a Michigan scientist by the name of C. Dennis Simpson studied the length of various blows on the DataMaster. The DataMaster is the machine used in Michigan to test a drinking driver’s breath.

Dr. Simpson’s study involved 60 male subjects. He tested each subject with either a 6 second blow or a 24 second blow.

In Simpson’s study the first exhalation breath sample was titled “DataMaster-Short Duration Exhale” (DM-SDE) and the second exhalation breath sample was titled “DataMaster-Long Duration Exhale” (DM-LDE).

The study found that the minimum deviation between the DM-SDE and the DM-LDE was .02 and the maximum deviation between DM-SDE and DM-LDE was .04. Furthermore, his study found that the probability of the .04 difference was 15% with the DM-LDE.

But it’s not only the length of the blow that might impact the breath test result. According to Dr. Michael Hlastala[viii] other factors play a role, such as: inhaled volume, hypoventilation or hyperventilation prior to the breath test and rate of exhalation (fast or slow).

Partition Ration Problems

Another fundamental scientific principles underlying breath testing is “Henry’s Law.” Basically, in a closed system there is a ratio of the amount of a volatile like alcohol in the gas above a liquid and the amount of alcohol in the liquid itself.

The closed system in breath testing is thought to be deep lung air because it is thought that it is in the deep lungs that blood alcohol and breath alcohol have reached equilibrium.

In the United States all breath testing equipment is set to assume a partition ratio of 2100/1.

A big problem with this 2100/1 assumption is that the lungs are not a closed system but instead are an open system. In an open system, as exists in human breathing, research has demonstrated a variance in actual partition ratio between 1555 to 1 and 3005 to 1 (Dubowski, 1985).

This indicates that a fixed partition ratio of 2100 to 1 for all ABT tests will underestimate the BrAC 77% of the time and overestimate the BrAC 23% of the time given a normal distribution of the subject population in the post-absorptive phase.

According to Simpson:

Unless the issues of meaningful variances among individuals regarding partition ratio and vital capacity can be resolved it is improbable any duration of exhalation can assure a valid breath alcohol result, excluding a significant error rate. The inference from this is to identify and use a bodily alcohol measure, such as whole blood, which has a very minimum error rate.

Because of the thermodynamics of this open system problem, Jones, in 1983, indicated the alveolar alcohol core partition ratio would be 1756 to 1 instead of 2100 to 1.

The DataMaster Discriminates Against Older Drivers

Simpson found that the 15% deviation increased with age. Specifically he indicates:

Furthermore, findings of this study suggest that the reliability and validity of ABT (alcohol breath test) results may be further compromised by age. This finding may be related to changes in lung functioning over time. Research has shown that lung function declines with age, especially if disease or injuries have affected the lungs (Griffith, et al., 2001; Knudson, Clark, Kennedy, & Knudson, 1977; Turner, Mead, & Wohl, 1968). Hlastala and Anderson (2007) have found that breathing pattern and lung size influence ABT outcomes. It seems possible that overall lung functioning may also impact ABT readings, such that outcomes become more volatile and less reliable with decreases in lung functioning. This represents a promising avenue for future research.

Obtaining the Data on Your Breath Test Result

One way to know if this .04 variation occurred in your case is to review the COBRA data from the machine.

According to Mr. Workman, “most evidentiary breath testing machines have the ability to transfer electronically the vital components of every breath test administered. The vital data is usually stored on a machine managed by the breath testing agency that manages the administration of breath tests within the jurisdiction.”

To obtain this information your attorney will need to ask for it in his/her discovery demand which might say something like:

“For instrument # XXXX please provide in digital format all of the data and records for all of the files downloaded and subject tests administered between X date and X date.”

Mr. Workman further states in his white paper that “many states closely guard their data, and Judges will not permit a defendant to learn about tests given on the same model machine, or even learn of tests administered to other citizens on the same machine.”

Some states actually publish their data on the internet. Such states include Florida, Washington and South Carolina. If you live in one of these states your attorney may be able to obtain internet access to this information.

If you have been arrested for drunk driving and believe that your breath test is too high contact the Barone Defense Firm today for a FREE case review.

[i] Simpson,Varying Length of Expirational Blow and End Result Breath Alcohol, International Journal of Drug Testing, Vol. 3. 2003.

[ii] Id.

[iii] Workman, Measuring the Subjective1 Component of Breath Testing for Alcohol: A Study of the Florida Breath Testing Data, 2008.

[iv] Thomas Workman is an Attorney, licensed in Massachusetts and before the US Patent Office. He operates a Forensic Consulting business, providing analysis and testimony concerning legal matters that incorporate computers and how computers produce evidence that is for Judges and Juries. Tom operates a website,computers-forensic-expert.com, upon which his current Curriculum Vitae can be found.

[v] Workman, Measuring the Subjective1 Component of Breath Testing for Alcohol: A Study of the Florida Breath Testing Data, 2008.at pg. 2.

[vi] Simpson,Varying Length of Expirational Blow and End Result Breath Alcohol, International Journal of Drug Testing, Vol. 3. 2003.

[vii] A.W. Jones, Physiological Aspects of Breath-Alcohol Measurement Alcohol, Drugs & Driving, Vol.6, No.2 (1982).

[viii] Michael Hlastala of Seattle, Washington is a Professor Emeritus of Physiology and

Biophysics and Medicine at the University of Washington. He has extensive training in them field of Respiratory Physiology. He offers Consulting Services for DUI-DWI cases involving chemical testing and field sobriety testing. He has authored or co-authored over 400 papers and articles. He can be reached at [email protected].