As originally conceived the United States Supreme Court was intended to be a final check on the police power. And to a lesser extent, so it is with all judges, who collectively form one of our three branches of government.

The central goal behind the idea of having three branches of government is that a separation of power would exist such that each branch would keep the other from gaining too much power.

Because of this there has always been a certain amount of tension between the branches and there has also always been a certain amount of overlap between them.

Take for example the executive branch, which is largely made up of the military and police powers. Both exist to protect us from local and foreign aggressors. One question that arises in this context is this: “do judges also have a role in protecting society?”

This is not such an easy question to answer, but it is a question that is often at raised when judges are interpreting criminal laws and the corresponding constitutional rights and the protections that pertain to them.

One such right is to be free from unreasonable searches and seizures. Out of this constitutional protection arise the limitations on the police power and ability to stop motorists.

Nowhere is this right more frequently litigated than it is in drunk driving cases. Nearly every drunk driving arrest is preceded by a vehicle stop, and so the analysis of a drunk driving case begins with the question: “was the stop lawful?”

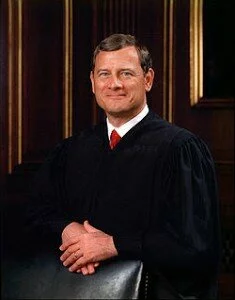

Justice Roberts

The view of many judges is that drunk driving is such a societal problem that attacking it justifies an expansion of the police power. This sentiment is certainly reflected in the Associated Press story entitled “Roberts speaks out on drunk driving case.”

Justice Robert’s opinion, as reflected in this story, is that “police should have every legitimate tool at their disposal for getting drunk drivers off the road.” In the Justice’s opinion, the ends justify the means because drunk driving is such a big societal problem.

And this brings back again to the question: “do judges also have a role in protecting society?” The answer is unequivocally “yes,” but only when followed by “so long as doing so does not violate the constitution.” Too often do judges see themselves not as a check on law enforcement, but instead as part of the law enforcement team.

Perhaps that is why the judge is so focused on how the high court’s decision may limit the ability of the police to stop a drunk driving. Robert’s said “The decision below commands that police officers following a driver reported to be drunk do nothing until they see the driver actually do something unsafe on the road — by which time it may be too late.”

Unfortunate yes, but for any constitutional question there will be a concern about how limiting the police power will correspondingly limit the efficiency of law enforcement. But the constitution is designed to limit the efficiency of the executive branch, and a Supreme Court Justice should never lament this fact.

Lest anyone think this opinion is only one held by a “conservative” judge (Roberts was appointed by the first Bush), liberals clearly also hold a “get tough on drunk driving” animus.

This is evidenced by the recent New York Times editorial lauding California’s new Interlock law. The editorial states:

“Mandating the ignition-interlock devices for all drunken-driving offenders is smart safety policy. Once installed, the vehicle will not start until the driver first blows into the device and registers an alcohol level below the legal limit.”

This opinion of the opinion maker’s paper is simply off the mark and not well thought out. The reasons have already been addressed elsewhere on this blog.

A drunk driver is unquestionably a danger to society, but the danger posed by a drunk driver pales in comparison to a judge or a police officer who does not follow the law.

{ 1 trackback }