As described in the previous article, it is important for DUI lawyers to understand how transdermal electrochemical alcohol testing works, and sometimes, how it does not work.

It is also important for DUI lawyers to have a good understanding of the case law surrounding this type of alcohol testing. In this regard, there is a new case out of Indiana that is of interest to DUI lawyers. The caption is:

MOGG v. State, Indiana Court of Appeals, 2009, No. 29A04-0902-CR-82.

Here is a Brief Summary of the Case:

On January 16, 2007 Appellant Mogg pled guilty to operating a vehicle while intoxicated. Her jail time was suspended pending successful completion of probation. A condition of probation was total non-use of alcohol. On August 27, 2007, the state brought its first allegation Mogg violated her probation by consuming alcohol.

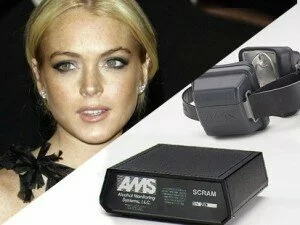

Mogg admitted to the violation and therefore, the trial court extended her probation and imposed an addition condition. In order to monitor compliance, Mogg was ordered to wear a SCRAM bracelet.

In January, 2008 Mogg’s SCRAM was replaced by a SCRAM II bracelet, which is an updated version. About three months later, on March 17, 2008, Mogg admitted to a second probation violation. This time the court simply extended the term of probation by four months. The SCRAM II condition remained.

On June 20, 2008 the State filed what appears to have been a third probation violation, again alleging that Mogg violated the terms of her probation by consuming alcohol “as evidenced positive SCRAM events.” On November 1, 2008 the State filed a fourth violation probation alleging that Mogg had consumed alcohol four days prior. The State’s allegation that Mogg had used alcohol was supported by positive alcohol readings from the SCRAM anklet.

Mogg did not admit to the third and forth violations so the trial court held an evidentiary hearing. After the hearing, Mogg’s probation was revoked based on the court’s finding that she had consumed alcohol. Mogg continued to deny consuming any alcohol.

Mogg appealed the court’s ruling on the question of whether the trial court abused its discretion by admitting SCRAM-based evidence of her alcohol consumption. An additional question before the appellate court was whether there was sufficient evidence to support the revocation of probation.

At the hearing the following testimony was received relative to the device:

The SCRAM bracelet electronically transmits, every thirty minutes, transdermal alcohol readings through a modem in the person’s residence to an AMS central computer. An AMS technician monitors the flow of data, AMS analyzes the data, and AMS and its local service provider (here, Total Court Services, Inc.) notify the probation office supervising the person when the data indicate alcohol consumption of more than one drink per hour for an average person.

On December 18, 2008, the trial court entered findings of fact in which it found SCRAM’s theory and technique had been tested, had been subjected to peer review and publication, had a known error rate, were subject to operational standards maintained by AMS, and were accepted in forty-six states. In addition, the trial court found the testing and studies of SCRAM I applied equally to support the reliability of SCRAM II

Discussion and Litigation Tips

This is a very useful case because it contains a great deal of information about the SCRAM and some excerpts from the testimony of Jeffrey Hawthorn. For example, the opinion indicates that (according to Hawthorne’s testimony):

Transdermal alcohol concentration (“TAC”) rises and falls on a curve that lags four to five hours behind the curve of blood alcohol concentration, as it takes longer for alcohol to be perspired through a person’s skin than to be absorbed into the bloodstream.

This 4-5 hour lag time is slightly higher than has been previously reported, and is important information to understand when defending an alleged blocking or tampering violation. Hawthorn also testifies that the SCRAM will only report an alcohol episode if the wearer has more than one drink per hour. Consequently, it seems clear that the SCRAM bracelet does not monitor total abstinence. Here is how Mr. Hawthorn explained this:

The SCRAM system “does not `flag’ an event until three consecutive readings exceed [TAC of] 0.02%,” which the average person reaches only with “more than one drink in his or her system. This gives the wearer the benefit of the doubt.” Transcript at 299. When an alcohol consumption event is indicated, the person is given an opportunity to provide AMS with an alternative explanation for the positive readings, such as an environmental “interferant” or other non-beverage alcohol exposure. Id. at 312. AMS technicians are trained to distinguish the TAC curve resulting from a true drinking event from one that is the result of an interferant.

In his testimony Hawthorn also indicated that the SCRAM device is a “semi-quantitative” screening device for determining “whether a person consumed a small, moderate or large amount of alcohol.” Id. at 290. This also comports with the scientific literature, all of which agrees that BAC and TAC are not the same, and that TAC is not a reliable quantitative measurement of BAC.

Hawthorn also testified that AMS has tested the accuracy of the SCRAM system in a study involving 839 total events, which registered 62 true positive drinking events and one false positive.

There is also a discussion in the opinion about the NHTSA. The opinion indicates:

The second study (the “NHTSA study”) was a November 2007 report of the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which involved twenty-two persons who wore SCRAM I over a period averaging four weeks per person and engaged in laboratory-dosed and self-dosed drinking totaling 271 episodes. The study concluded SCRAM I had no “false-positive problems when true BAC was <.02 g dl. id. at the problems identified with scram i were false negatives and that bracelet sensitivity accuracy declined over duration of wear. hawthorne testified ii involves same technology scientific principles as only difference between two units being components are smaller fit one case rather than in cases.>

The opinion’s conclusion that there were “no false positives” in the NHTSA is questionable. Nevertheless, this opinion does contain a basic discussion of how the SCRAM anklet works, how AMS monitors the equipment and how a problem is determined and reported. There is also a basic discussion of the literature on SCRAM.

Get a FREE confidential CASE EVALUATION on your Michigan OWI/OWVI/DUI by calling (248) 306-9159 , or filling out this consultation request form. Call now, there’s no obligation!

{ 1 comment… read it below or add one }

THE 2007 STUDY ALSO REMARKS THAT THERE WAS NO CONTROL GROUP, I.E. NO PEOPLE TOLD NOT TO DRINK TO IDENTIFY ANY FALSE POSITIVE RATES AND THEY SAY IN THE FINAL STUDY THAT THIS WAS NOT FOCUSED ON SO THEY DO NOT HAVE AN ERROR RATE TO REPORT. READ IT CAREFULLY. THERE ARE MANY HOLES- NAMELY THE REASONS FOR THE UPGRADE TO THE SCRAM II. THERE WERE WATER PROBLEMS WITH THE “O-RINGS” INSIDE CAUSING A DECLINE IN ACCURACY. APPARENTLY THE UNIT DID NOT VENT OUT WATER AFTER ABOUT 3 WEEKS OF WEAR AND THIS RETENTION OF WATER CAUSE PROBLEMS WITH THE SENSORS.